By Andrew Drever

October 8, 2004

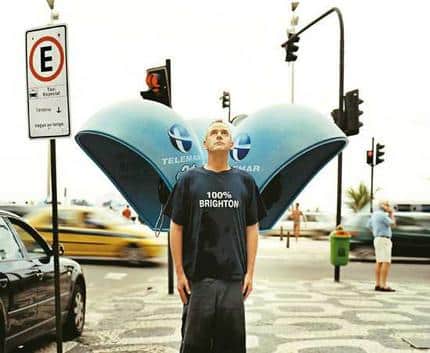

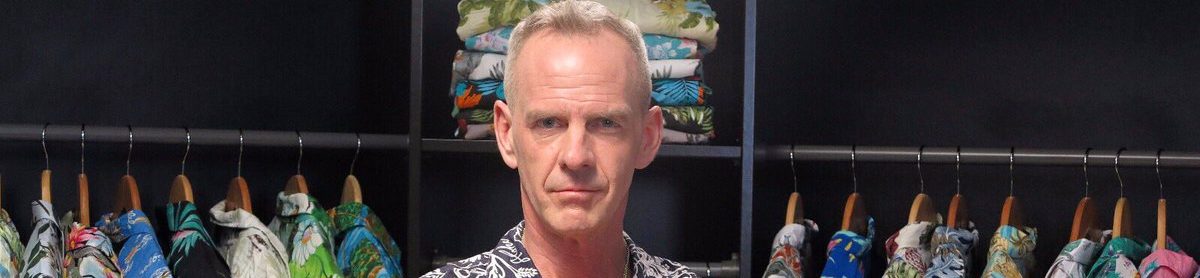

Norman Cook, aka Fatboy Slim, has rebuilt his marriage and his sound for new album Palookaville, but he doesn’t want to end up in the goldfish bowl of fame again.

I alight from the train at Hove, just one station down the coast from the British seaside town of Brighton. Jumping into the cab, I show the cabbie Norman Cook’s address.

He smiles and nods.

“You’re going to Fatboy Slim’s place, then?”

Welcome to Palookaville.

Norman Cook, or Fatboy Slim, is one of Brighton’s best-known residents. The DJ-producer is a local celebrity who’s lived in the area for 22 years, staged two much-publicised dance parties on its beach, run nightclubs in town and has even been helping out the local football team in need (he’s been leading the campaign for a new stadium for Brighton and Hove Albion).

He’s well-liked locally, and the cabbie confirms he’s “one of the nice ones”. He’s picked Cook up a few times, he says, and the star always has time for a friendly chat. Not like other nameless “wanker celebrities” in the area, he intimates.

Cook’s local popularity, however, hasn’t stopped the dance star from taking a pounding from the British press in the past couple of years. He’s had the sort of tabloid attention any “shy show-off” (as he would later describe himself) would prefer to avoid.

In July 2002 he endured a massive media fallout when 26-year-old Australian nurse Karen Manders died after falling from a railing at his Big Beach Boutique party on Brighton Beach, an event that attracted a chaotic 250,000 revellers to the quiet seaside town.

Then, in January 2003, there was his very public bust-up, and subsequent reconciliation three months later, with his wife, radio DJ Zoe Ball. When Ball first announced the split to the media, she also admitted to her affair with another DJ-producer, Dan Peppe, of little-known British dance outfit Themroc.

During the marriage breakdown and subsequent media feeding frenzy, Cook discovered his phone was bugged, and photographers were camping out and shooting off rolls of film from among the rocks on the private beach in front of his house. He felt like a “hunted animal”, he says, but ever cheerful, stresses that the press attention he gets is mostly good.

“I’m not complaining,” he says with a shrug. “You live by the sword and you die by the sword. If you want to be a show-off, then you have to take the bad with the good.”

It’s the world’s music press, then, that have been summoned to Cook manor at Hove Beach so he can spruik his new Fatboy Slim album, Palookaville.

Cook owns two houses side by side on the private stretch of beach that he shares with neighbours such as former Beatle Sir Paul McCartney and actor Nick Berry (EastEnders, Heartbeat). One of his houses is where he lives with his wife and four-year-old son Woody, and the second contains his studio and office. I’m dropped off at this latter “working” house after a short cab ride, and I walk into a media circus.

There’s a Japanese photo crew lounging on an outside patio that backs onto the beach. The Palookaville album is blaring from a stereo in the corner, and two other reporters drink beer at the kitchen table. Cook’s eccentric assistant, Jim (who resembles an older version of Disco Stu, the cult character from The Simpsons), is buzzing around, as is a record company representative from London who’s making sure things run relatively smoothly.

I’m quickly introduced to Cook, who’s tanned and dressed down for the occasion in shorts, a T-shirt and thongs. He bounds up and down the stairs, cracking jokes and posing for the Japanese crew on the beach, self-consciously grinning and giving me the two fingers up while I’m watching the photo shoot from inside.

The two whitewashed houses are vast but not extravagant. There are Polaroids stuck to the fridge in the kitchen showing Cook (wielding an acoustic guitar) and Ball indulging in a hearty singalong with friends, plus other casual shots of Norman with Ball and Woody.

I’m the last cab off the rank on day two of the three days of press for the new record, so the silence is deafening when the last reporter leaves. Cook visibly relaxes, offers a beer or tea, and hunches over a laptop computer to watch the crazed video of his new single, Slash Dot Dash, directed by veteran British video director Tim Pope (Talk Talk, the Cure, Soft Cell).

He’s delighted with the result, laughing uproariously, and then beckons me upstairs to a stylish recording studio lounge, where the french doors open out to a massive outdoor balcony overlooking the glistening English Channel and the stony, graceful beach.

Despite the questions Cook has faced over the past couple of days, and the slight difficulty he has in talking after breaking his nose and injuring his mouth in a nasty sleepwalking accident in Portugal two months earlier (where he was DJing as part of the Euro 2004 football tournament), he’s relaxed, warm, friendly, humorous, enthusiastic and talkative.

New album Palookaville is similarly fun, funky and frivolous. After the darker tones and the more caustic bangers of his last album, 2000’s Halfway Between the Gutter and the Stars, this LP sees a looser, baggier Fatboy Slim. It took a few attempts to get it right, though. Cook began two different albums but scrapped both, realising his best work is when he “kicks back and has a laugh”.

Cook cites production work he did with Blur in 2002 as a big influence on this album’s sound. After grappling with some fruitless early recording sessions for his own album, he took a break and flew to Morocco to produce tracks for Blur’s Think Tank. Particularly concerned at the time about the rapid decline of dance music, the trip cleared his head, and observing a band collaborate helped him find the inspiration he’d been lacking. It sparked his desire to use live instruments on Palookaville, rather than just his usual trusty sampler.

“It mellowed me out, ” he says of the Blur experience. “It mellowed me out about collaboration with other people. I remembered that I used to play bass and guitar! There would be times if Alex (James) wasn’t in the room, I’d be playing bass, and in the absence of Graham (departed Blur guitarist Graham Coxon), Damon and I were sharing guitar duties. There’s also the camaraderie. I realised I work on my own pretty much most of the time, so when things are going wrong I have no one to chat to, have a joke with or bounce ideas off. I just think gradually I became more open to the idea of collaborating with other people.”

Palookaville features guest vocalists such as DJ Shadow’s Quannum Collective rapper Lateef the Truth Speaker, Damon Albarn, dance producer Justin Robertson and previous collaborator Bootsy Collins (on a silly remake of Steve Miller’s The Joker). It also found Cook, who was bassist for late-’80s indie heroes the Housemartins, picking up his bass again, and enlisting the services of unknown local band Jonny Quality.

Highlights from the album include Lateef’s dusty cowboy rap on the hazy trip-hop of The Journey, the gospel-influenced darkness’n’light of Push and Shove, the laconic return to funk form on Don’t Let the Man, and the summery groove of Wonderful Night.

Many are touting Palookaville as a return to the funk of a previous outfit of Cook’s, Freak Power, a collective that imploded after just one album, in 1997. He doesn’t disagree, although he has reservations – and bad memories – from the time.

“Every time someone says that it sounds a bit like Freak Power, I always wince and go, ‘Oh, shit!’ I don’t know. Maybe. It’s probably me going back to classic song structure rather than just mindless repetition. Plus, my love of funk music is always going to sound a bit like that.”

The new album definitely has some strong commercial prospects, and those at his record label Skint are particularly excited about its potential.

In 1998, Cook had a hit album with his second Fatboy Slim record, You’ve Come a Long Way, Baby. His Australian tour as part of the Big Day Out in early 1999 coincided with the massive breakthrough of his Praise You single, and at the time he was one of the biggest dance-music artists in the world. Follow-up Halfway Between the Gutter and the Stars was a strong seller, but didn’t scale the commercial heights of the previous release.

So, what are his expectations of Palookaville? Is there a desire to return to where he was in ’98-’99?

“I’d like to return to that kind of place,” he says measuredly, “but not actually that place. I mean, You’ve Come a Long Way, Baby had been out four months and it went up to No.1 and knocked Robbie Williams off the top. You have to take on the pressure at that point. You become a money-making machine for so many people and you have to fight them for your own free time.”

He pauses.

“I personally think it’s (Palookaville) the best thing I’ve ever done, and a lot of people are saying that, but it’s kind of scary, because if it gets as big or bigger than You’ve Come a Long Way, Baby, I’d probably run a mile. It’s not what I wanted. You don’t want to be in the goldfish bowl. I never wanted to be the centre of attention all the time – only some of the time!”

If anyone knows what it’s like in the goldfish bowl, Cook and his wife do.

He does me the favour of bringing up the topic of their split and reconciliation and seems more than happy to talk about it, in general terms anyway.

“I know how a fox feels when he hears a dog barking,” he says of the time. “It just gave me an insight into how scared you can be when you realise everyone’s staring at you and some of them are out to get you. I had to get my strength back and to be able to come out and stick my head back into the lion’s mouth.

“Zoe and I are just coming up to our fifth wedding anniversary and we’re really chuffed that we got there. I mean, I nearly lost it. A year-and-a-half ago I nearly lost the lot. It scared the shit out of me and I had to put my priorities in order. I was lucky enough to get a second chance and I’m damned if I’m going to f— it up again.”

Cook says he and Ball got through that time by putting much of their respective workloads on hold and wholly concentrating on repairing their marriage.

“It took a lot of work to get married in the first place,” he says, “and it took a lot of work to put it back together when it went wrong. We’re determined that we’re not going to let that happen again. And if this album really does happen to blow up, it’s going to put a lot of pressure on me just to keep enough plates spinning. If it’s a big hit, there will be pressure on me to perform, perform, perform, I’m really going to have to say, ‘Actually, you know what? This time around, I’m not going to do that. My family’s more important.'”

As if right on cue, assistant Jim enters the room.

“I’ll pretend I didn’t hear that,” he sniffs, before wrapping up our interview.

Afterwards, Cook is happy to pose for my photos, then walks me downstairs while chatting away and finally calls me a cab.

“One of the Japanese reporters said that dance music has been waning,” he says before I leave, “and they said that I’m the person who is about to save it!”

He laughs.

“I’m like, ‘Well, that’s really nice of you to say, but it’s a hell of a responsibility!’ I’m not even sure if this is a dance record anyway. But I’m really excited about it, because I’m kind of confident it’s not going to fall flat on its face. I’m kind of confident that it’ll do well. There is an outside chance that it might do really f—ing well, in which case I find that really daunting, because I’ve been through that before, and I know it’s scary.”

Palookaville is out next week on Skint/Sony.

source: www.theage.com.au

Be the first to comment