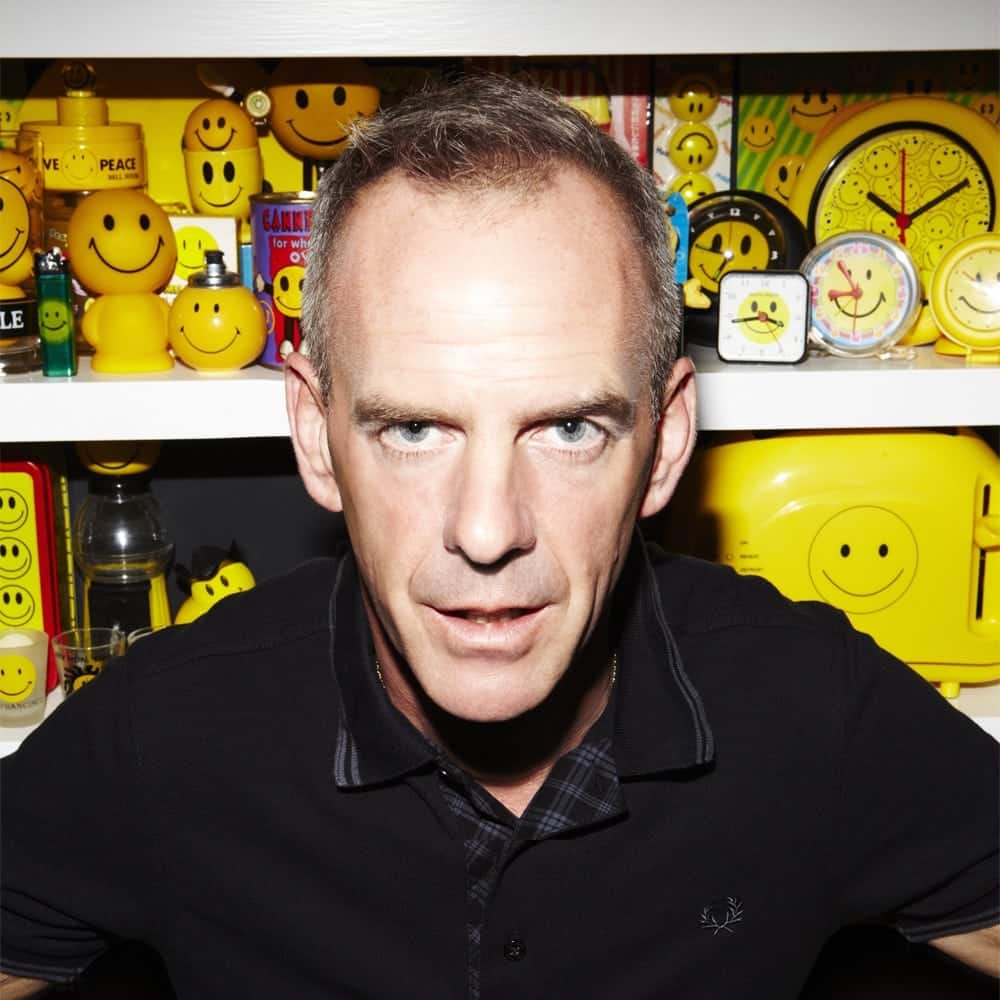

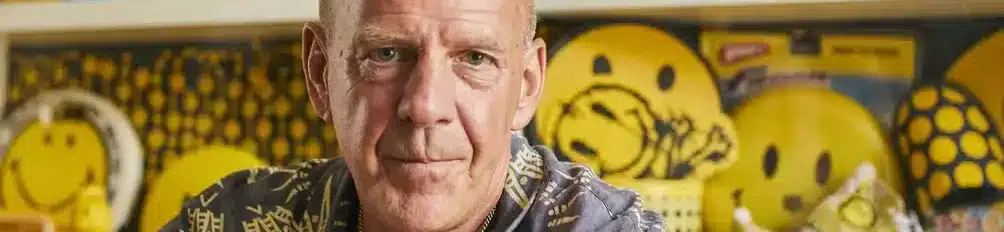

Upon entering Norman Cook’s home in Brighton you notice two things. The first is his stash of awards — a handful of Brits, a smattering of MTV men on the moon, a Tim Lovejoy-signed football that commemorates a hat trick of appearances on Soccer AM. The second is an unignorable luminous cabinet stuffed to the brim with the ever-grinning icon of everything from San Francisco hippy-dippyism to the raw rumbles of acid house: the smiley.

The smiley, and the smile, and the notion of smiling and smileyness, become inextricable from Cook as a person when you’re in his presence. He’s perpetually on the verge of flashing teeth throughout our conversation, always ready to cut through any self-seriousness with a bit of self-administered pomposity-pricking.

I beamed down to the Brighton seafront on a blustery morning. Waves plashed against the windows of Cook’s lounge as we talked. I’d been invited down, nominally, to discuss a triumvirate of subjects: his Smile High Club, the twentieth anniversary of his record label Skint, and the reissue of his 2000 album, Halfway Between The Gutter and The Stars.

I don’t need to run you through his storied career as a producer, remixer and DJ. Even those of you who devote weekends to banging out the B2 on Berceuse Heroique cuts in damp basements will have come into contact with his work as Fatboy Slim. He’s the Hawaiian shirted DJ your mum nods her head to in the car, he’s the mainstage mainstay your just-out-of-puberty brother’s pumped to see this summer, the wizened warhorse who’s soundtracked a thousand lower league football matches. He’s an indelible part of contemporary British culture, a remnant of a past that swapped promise and hope for Chris Evans’ Mail on Sunday magazine column. He is, as he says himself, “a bloke playing records and waving his arms about.”

The past edged it’s way into our conversation, as it tends to do, but for the main, Cook was focused on where he’s at now, and where, as a 51 year old father of two, he’s going next. The current plan is to take things sideways. He’ll begin this process at Creamfields and SW4 this summer. “I’ve played them both so many times, so we decided to branch out and I was asked to run an arena, he tells me. “I’ve kind of done that before but generally what happens is that you get to pick a few of the acts and you maybe do a bit of branding. Last year it was the Eat Sleep Rave Repeat stage but I wasn’t that involved with it outside of branding. We were talking about how to brand it, how to make it different, how to make it ours. We wanted to create a vibe within an enormous structure that made it feel like it wasn’t just another tent at another festival. So we did some brainstorming and had a few blue sky thinking sessions and came up with the Smile High Club.”

For the uninitiated, Cook’s not about to ask revellers to join him in an EasyJet loo for a bit of loving at 35,000ft. Rather, four lucky fans will be pinged from gig to gig in a private jet. “They’ll be flying between gigs while I’ll be driving, so they’re even more VIP than me,” Cook says. What might be seen as a slightly show display of financial security in a time of economic unrest makes slightly more sense in the context of the Random Acts Of Smilyness campaign that Cook and his team are integrating into their festival experience over the summer. Any personally held belief about the possible triteness of such a scheme — and despite it’s happy-chappy-all-in-it-together ethos, it is undeniably a well done bit of branding and marketing, a carefully crafted and planned scheme — melts in the face of his toothy positivity. Explaining the concept to me, he’s adamant that it’s about inclusion and fostering genuine euphoria and communality. “I’ve always been about communicating with the crowd and making them smile as well as dance. Some people are all about the twisted underground and sometimes I wish I could do that.” There’s a millisecond of hesitation, the smile seems to vanish imperceptibly for the shortest of split seconds. “But it’s not my forte. I’m not knocking people who are serious about the music because I am too. But I’m also serious about having a party.” He’s smiling again.

That smile doesn’t lull you into a false sense of security, per se, but it can occasionally be disarming. You find yourself forgetting that the bloke sat on his sofa opposite you — in a very lived in lounge — isn’t just someone who spins party tunes down the pub on the Sunday night before bank holiday Mondays until you find yourself asking about how it feels to play to a quarter of a million people on a beach (“I had the police breathing down my neck telling me that if one thing goes wrong the whole event’s off. They said to me, “someone will die tonight.””) or if ‘superstar DJs’ ever actually feel like superstars (“It’s sort of embarrassing because you don’t want to say, ‘yes, I am a superstar DJ,” But you do feel like a superstar, and you get treated like a superstar”). When Cook’s first career — as bassist in Hull-based jangly miserablists the Housemartins — came to a gradual end, he threw himself into his new one wholeheartedly but never imagined that what followed would. From acorns (a remix of Eric B and Rakim, early solo productions like the chart-smashing “Dub Be Good to Me”) came gargantuan oaks.

We zoom back to those heady early days of the late 80s. Here in 2015 we seem to be set for a second, second summer of love. While acid house never really left clubs, it hasn’t felt this prevalent, this there for years. Cook witnessed its birth here in the UK. “That was the first second summer of love and the summer I moved back to Brighton from Hull because 1988 didn’t happen till about 1991 in Hull. All my mates were wearing smiley bandanas and going ‘acieeeeeed’ and I thought, what are you on about? So they took me to Tonka and gave me a pill.” For the uninitiated, the Tonka parties were legendary blow-outs that spilled out onto Brighton beach, headed up by the inimitable DJ Harvey and his mate Chocci, amongst others. “They had a fanatical following who knew they put on the best parties in terms of the music, the setting and the atmosphere they engendered,” Cook says. “That was the first time you’d really seen the DJ elevated to godlike status. The fact that Harvey has this Jesus-y look about him helped. There’s people my age who go gooey-eyed when they remember those parties.”

Tonka’s freewheeling mix of everything that came to be known as Balearic and then-naescent aicd house was an eye-opener for the former indie-rocker, but it was Terry Farley and Andrew Weatherall’s Boy’s Own crew and a weekend at Butlins in Bognor Regis that provided Cook with his euphoric moment of epiphany. “My mates dragged me down and I’d never really got the acid thing. I saw Darren Emerson, which I only found out years after. I was telling him this story about seeing someone play two copies of “I’ll Be Your Friend” by Robert Owens and everyone was hugging each other, hands in the air, and my head just went “woooosh, I get it!”” he says. “It was all those acidy noises that work with ecstasy. So I told Darren about it and he said, “Yeah, that was me DJing!” That was the moment. Aside from doing hip hop stuff, that was the moment I started making house.”

When questioned about why we seem to be intent of reviving everything ever, Cook is convinced that the flashy, flashing, flash in the pan juggernaut of EDM is responsible. “I think people want to reclaim house back from EDM. Either by being purists or acting in a more pure fashion. It’s about trying to get house back to what house was and reclaiming it from the more commercial end of things.” While Cook is, and has always been, a populist choice and a commercial draw, he sees himself as a totally separate entity to the current stadium-ready acts that have seen Bud-chugging fratboys swap Kid Rock for Kaskade. “It’s fine as entry level stuff, but make no mistake: EDM will crash and burn. It’s based on a pyramid scheme of making money and as soon it stops making money the whole house of cards will fall down. We want there to be something left when this bubble bursts.”

The past seems to be a territory he’s unwilling to traverse for the sake of it. As nostalgia washes over us like the fine rain that pelts Cook’s windows, I decide to ask if feels we’re too indebted to the past because we’re living in a moment when our culture — club culture, ecstasy culture, Ibiza culture, house culture, techno culture — has become a staple of everyone’s experience of the popular, a cultural bedrock that’s understood by all. “Nostalgia is based on wanting to return to old values by trying to experience the way things were done,” he begins. “Whether it’s people recreating medieval battles or building yurts, it’s all about trying to engender lost values. Everything that’s happening in dance music now is people wanting to go back to a genuine euphoria, rather than the ersatz euphoria that’s generated by big synth pads.”

Before I made my way back into the perfectly overcast English day I had one final question for Cook. After playing every festival ever, after selling out arena after stadium, how does a man dedicated to making others smile make himself smile? “I’ve got a little ritual: I drink about three Red Bulls, take my shoes off, put the Hawaiian shirt on and that gets me into character. Just before I go on stage my tour manager slaps me really hard across both cheeks so I go on stage fighting. As soon as I’ve got more than ten people who are excited about it, as soon as I latch onto that, my mindset reverts back that to a very high 17 year old.”

We leave him, grinning away.

In addition to the reissue of Halfway Between the Gutter and the Stars (available now) and the very recently released 4CD set The Fatboy Slim Collection, mid-August sees the release of the 20 Years of Being Skint compilation. Why not get in the mood for a summer of Fatboy by streaming this exclusive remix below?

Follow Fatboy Slim on Facebook // Twitter

source: thump.vice.com

Be the first to comment